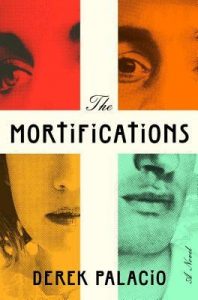

Title: The Mortifications by Derek Palacio

Title: The Mortifications by Derek Palacio Published by Tim Duggan Books

Published: October 4th 2016

Genres: Fiction

Pages: 320

Format: Hardcover

Source: Blogging for Books

Goodreads

The sin is in the knowing. The sin Christ confronts in the desert is the knowledge that his body is useless and, dangerously, how easily he can dismiss it. He will see how tiny a thing he is doing. He will know how small he is as a human being, how little he can change the world as a lump of flesh. The moment he knows, he can and will and should let it all fall away. He will enact the right of a God on Earth; he will make food from stone. He will shake water from the clouds. He will walk into a city and take it.Derek Palacio’s stunning, mythic novel marks the arrival of a fresh voice and a new chapter in the history of 21st century Cuban-American literature.

In 1980, a rural Cuban family is torn apart during the Mariel Boatlift. Uxbal Encarnación—father, husband, political insurgent—refuses to leave behind the revolutionary ideals and lush tomato farms of his sun-soaked homeland. His wife Soledad takes young Isabel and Ulises hostage and flees with them to America, leaving behind Uxbal for the promise of a better life. But instead of settling with fellow Cuban immigrants in Miami’s familiar heat, Soledad pushes further north into the stark, wintry landscape of Hartford, Connecticut. There, in the long shadow of their estranged patriarch, now just a distant memory, the exiled mother and her children begin a process of growth and transformation.

Each struggles and flourishes in their own way: Isabel, spiritually hungry and desperate for higher purpose, finds herself tethered to death and the dying in uncanny ways. Ulises is bookish and awkwardly tall, like his father, whose memory haunts and shapes the boy's thoughts and desires. Presiding over them both is Soledad. Once consumed by her love for her husband, she begins a tempestuous new relationship with a Dutch tobacco farmer. But just as the Encarnacións begin to cultivate their strange new way of life, Cuba calls them back. Uxbal is alive, and waiting.

Breathtaking, soulful, and profound, The Mortifications is an intoxicating family saga and a timely, urgent expression of longing for one's true homeland.

Derek Palacio’s debut novel The Mortifications follows a Cuban family in the 1980s. Soledad Encarnación and her two children, twins Ulises and Isabel, leave behind a husband and father to escape the revolutions of Fidel Castro’s Cuba. Like many novels of families, this one has its share of interesting characters who all represent some aspect of humanity. Soledad is a mother trying to do the best thing for her children, Isabel finds solace and meaning in religion, Ulises finds himself through the classics and agriculture, and Henri becomes the stand-in father figure.

While I found the first half of the book incredibly engaging, I found the last half stretching for believability and substance. Palacio is a talented writer. However, I found some of the metaphors and similes and symbolism reaching a little too far at times. When I see a character named Ulises, I almost expect a Cuban expression of something resembling Homer’s The Odyssey. At first, the novel did feel like it would go in that direction, and it did, a little bit, with Ulises becoming fascinated by classics during a recovery period. I almost wonder, as I’ve seen similar things before in post-MBA debut novels, if this is a rite of passage, a stuffing of everything you’ve learned into one novel whether or not it actually works. I felt that there were also too many characters for how short this is. I think following one or two of the characters and their immigration experience (and even their return home) would have made for a richer novel.

However, I did enjoy reading this, and I will recommend it to people interested in immigrant experiences and Cuban-American experiences.

Thank you to Crown Publishing/Blogging for Books for providing me with a copy in exchange for a review. All opinions are my own.

Title:

Title:

Title:

Title:  Title:

Title:  Title:

Title: